‘We’re Not Alone’: Preserving Group Therapy Through Videoconferencing During COVID-19

‘Our greatest strength’ interrupted

As the coronavirus surged the week of March 16, 2020, Julie Achtyl and Patrick Seche of Strong Recovery in Western New York made the tough, but necessary call to suspend their in-person groups for individuals with substance use disorder (SUD). These groups—which Achtyl calls “our greatest strength”—simply couldn’t operate given social distancing guidelines advised by the CDC and mandated by the state.

At this critical time, Strong Recovery’s opioid treatment program (OTP) was making sure that medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) would not be interrupted. Led by Seche, senior director of addiction services, the OTP was rapidly converting to curbside medication dispensing.

Strong Recovery staff prepared for curbside dispensing

During that large-scale conversion, Strong Recovery was tracking changing federal and state regulations, calling patients to stay connected and explain new processes, addressing staff concerns, and applying physical distancing and enhanced cleaning at its facility. To reduce traffic and proximity of personnel, a split schedule was developed in which staff alternated working at the clinic and at home.

Therapists provided individual therapy through telehealth (initially by phone) and in-person meetings as appropriate for patients’ needs. They were especially aware of added stress and isolation around the COVID-19 pandemic and the potential increase in overdose risk.

With physical distance as the new normal, patients and providers alike shared that they missed seeing each other at groups. They missed the support and camaraderie the meetings provided.

Groups are “the heart and soul of our program,” said Achtyl, program director of Strong Recovery’s outpatient clinic. “That’s why staff was asking for it again, patients were asking for it again, and it was absolutely essential for us to work through the barriers to figure out how to offer this service again.”

Changing guidance and growing confidence around HIPAA-compliant online platforms pointed to videoconferencing as a new meeting place for groups. Achtyl and Seche assessed this approach, which posed challenges in terms of operations and patient confidentiality. Strong Recovery was able to rapidly address and overcome these hurdles to offer a safe alternative to in-person groups.

At the end of April 2020, they had the new system up and running, just six weeks after groups were halted. The rollout was quickly scaled up to include 30 videoconferencing groups. These sessions supported clients during early and late recovery and as they faced the unique challenges of the pandemic.

Rooted in evidence

Videoconferencing group therapy has grown from two fields of evidence: 1) telemedicine-based treatment for SUD and 2) group-based treatment for SUD. Research supports the use of telemedicine in treating SUD, including opioid use disorder (OUD). Patient satisfaction and adherence for telemedicine are as good as or better than they are for in-person visits.¹ Evidence also indicates that group therapy promotes abstinence with SUD populations broadly.²

Research is building on the combination of telemedicine and groups as well. Three papers about conversion to videoconferencing groups (though not SUD specifically) during COVID are particularly relevant. Two of these discuss how Yale New Haven Psychiatric Hospital moved its outpatient groups for adults and adolescents online, integrating electronic health records.³ The third describes how McLean Hospital/Harvard Medical School converted its adult behavioral health partial hospitalization program to telemedicine, including group therapy.⁴ Published rapidly, these papers contain minimal outcome data; but they give detailed timelines and show full conversion in a matter of weeks. They report uniformly positive data on feasibility, attendance, and satisfaction, and none suggests adverse outcomes compared to in-person treatment.

Use of videoconferencing group therapy for SUD treatment makes sense for many reasons, including cost, scalability, and patient convenience, satisfaction, and adherence. While the research on this practice grows, the evidence on group therapy for SUD and on telemedicine for SUD suggests it is a sound approach, especially with the backdrop of COVID-19. As a recent paper on group dynamics and group treatment observes, “Our ability to engage socially while also protecting ourselves from illness makes online groups one of the most important resources during the COVID-19 pandemic.”⁵

Access in rural communities

Videoconferencing groups could help increase access to treatment for people in rural communities. According to a systematic review, “Home-based videoconferencing groups overcame known barriers for attending face-to-face groups” including travel demands. They “could be used to develop new and relatively low-cost interventions, particularly with at-risk groups such as those living in rural areas.”⁶ “Given the limited availability of mental health providers, especially in remote or rural areas,” another systematic review states, “it is reasonable to consider group-based treatment [through telemedicine] as a way to disseminate evidence-based care more broadly.”⁷ Barriers to telemedicine, including limited broadband internet, need to be addressed, however.

It’s important to note that videoconferencing groups can take different forms including:

Single point-to-point format: Patients come together in the same room and meet through telemedicine with a therapist who is at a different location.

Multipoint format: Patients join from separate locations through the video platform.⁸

The single point-to-point format could help in rural areas facing a shortage of clinicians or limited broadband. Participants do not need to have their own technology or internet access to join a meeting, and a provider outside the immediate area could facilitate. This approach requires a physical meeting space, however, plus a staff member onsite to manage technology and any patient needs that come up.

The multipoint approach, which also has the potential to expand services in rural communities, was better suited to needs during the pandemic and was the path Strong Recovery took.

Since travel and technology both pose challenges in rural areas, a blended format—in which space and technology are available, but joining from home is also an option—could be beneficial. Internet hotspots and support from the Universal Service Administrative Co.'s Lifeline program could help with broadband concerns.

Shifting gears

To implement multipoint videoconferencing during COVID, Strong Recovery staff had a lot to learn, and fast. They had to get comfortable with the technology and adapt their process as therapists to the virtual setting. Videoconferencing would be new for patients too; they would need support to navigate the platform.

Preparation throughout the month of April led to a launch of videoconferencing groups on April 27, 2020.

Achtyl took part in an educational series for behavioral health leaders to learn the ins and outs of telehealth by phone and video. She also consulted with the University of Rochester Medical Center Partial Hospitalization Program, which had already implemented video-based group therapy.

Strong Recovery staff met on April 17 to discuss reestablishing groups. From April 20 to 24, Achtyl trained staff on the video platform (Zoom). Meanwhile, therapists were surveyed about which groups should be offered online and when. (Strong Recovery's implementation timeline may help other organizations plan for a shift to video-based groups.)

Identified topics included Early Recovery (for patients still in active use) and Late Recovery (for patients who have obtained some level of sobriety). Additional specialty groups (more educational in nature) were chosen to address urgent needs during the pandemic, like Relapse Prevention, Family Dynamics, and Parenting Skills. After implementation, topics evolved based on patients’ interests and needs, and some were offered multiple times per week.

Roles and responsibilities

Leadership, administrative staff, and clinical staff contribute in key ways to videoconferencing groups’ success. The logistics of running a group-therapy session online also led to a new role: the meeting “host.”

Achtyl’s colleagues at the Partial Hospitalization Program strongly recommended having a host for each group to work behind the scenes and help patients individually while the therapist led the session. This advice was critical but led to a tough realization: Two clinical staff would probably be needed for each group. The alternative didn’t look good. Therapists would have a hard time facilitating if they were also troubleshooting on the video platform. To ensure a smooth process, Strong Recovery decided to use hosts.

Some hosts were therapists, but not all. Peers, counselor aids, and supervisors were also identified as a good fit because of their clinical experience. That experience allowed hosts to help individual patients who were in crisis or behaviorally inappropriate. They could pull those members out of group to a virtual “breakout room” to meet one on one, the goal of those discussions being to bring people back into the group.⁹

Seche and Achtyl were able to allocate clinical staff to the role of host. Programs with fewer clinical staff could approach the role differently. For example, an administrative staff member trained in the platform could be the host and manage the technical side of meetings. In that case, a clinician could be on call, able to join the meeting/breakout room in a crisis situation.

The responsibilities of each role in videoconferencing groups were mapped out and discussed during planning. Starting May 1, 2020, staff met for weekly huddles to talk about how the process was going and help each other navigate challenges.

Role | Duties |

|---|---|

Leadership |

|

Therapists |

|

Hosts |

|

Administrative/ |

|

Workflow

Strong Recovery developed a weekly schedule, with groups offered Monday through Thursday and weighted more heavily toward the afternoon. Medication dispensing, which takes place in the morning, was an important consideration in determining times. Schedules specified the therapist and host, the name of the group, and the time.

SAMPLE GROUP SCHEDULE:

Therapist/Host | Group | Time |

|---|---|---|

[Name/Name] | Young Adult Early Recovery | 10-11 a.m. |

[Name/Name] | Late Recovery | 10:30-11:30 a.m. |

[Name/Name] | Exploring Recovery Through Music | 12-1 p.m. |

[Name/Name] | Late Recovery | 1-2 p.m. |

[Name/Name] | Dialectical Behavior Therapy | 2-3 p.m. |

To help with their daily workflow, staff received instructions for setup to consult, covering steps such as:

Signing on securely to the electronic health record

Scheduling group sessions

Creating meeting links to send to patients (Note: Releases had to be obtained to email the links.)

Selecting settings in the platform that support security and improve functionality (e.g., waiting room, chat)

Managing logistics in meetings (e.g., breakout rooms)

Administrative staff ensured meetings ran smoothly through careful scheduling and management of meeting invitations. They paved the way for successful sessions through effective outreach and communication. They also helped patients and colleagues with technical issues.

Hosts had a lot to manage during the meeting itself. They manually admitted each participant (staff and patients) from the waiting room. They managed the chat box so the therapist could focus on the discussion. Patients were encouraged to use the chat only if they had technical difficulties or were in crisis so that it wouldn't interfere with the conversation.

Hosts also created breakout rooms when a one-on-one meeting with a patient was requested by the patient or therapist (which could be communicated via chat), or when the host identified the need. In cases where a patient was being inappropriate, the host could also turn off video/audio or send the patient to the waiting room.

The host could assign another staff member to serve as a “cohost.” At Strong Recovery, for example, the host made the therapist a cohost so they could both manage the features of the platform as needed. This step also provided backup in case the host was disconnected.

Financial considerations

There are staffing and technology costs involved in converting to multipoint videoconferencing group therapy. Staff considerations include the shift away from building security (since patients attend groups remotely) to adding more clinical hours to fill the role of host.

Subject | Considerations |

|---|---|

Costs |

|

Funding |

|

Space |

|

Training and skill development

Groups have the same purpose when held online: As Achtyl put it, they show us “we’re not alone.”

Reciprocal support in a group is different from the relationship between therapist and patient. “There is such power in the support that is received from other patients,” Achtyl said. An observation from a peer can resonate more than the same idea coming from a therapist. People with similar or different experiences can come together in group and find strength by discovering that “we’ve all been through some level of addiction, and we’re trying to figure out how to fight through it.”

Achtyl believes that the “support and accountability” group provides “is one of the greatest influencers of sobriety and why patients keep coming back.” Individual and group therapy are both important, but through the “connectedness and cohesion” they offer, “groups are really where the change happens.”¹⁰

Developing confidence, building rapport

Videoconferencing requires therapists to try new strategies to build rapport and group dynamics. Counseling is deeply rooted in emotional connection, and that can be harder to foster remotely. Through multifaceted training and openness to staff concerns, supervisors can support therapists’ success.

Achtyl met with staff individually to train them on the video platform and followed up with a larger session with staff. Training continued over time, including to prepare more people to handle the role of host. Achtyl found one-on-one time with staff to be particularly important for training and ongoing support.

Therapists learned tips for their first session that established the groundwork for successful groups. They shared “group norms,” adapted to videoconferencing, during this initial meeting. Hosts made sure to introduce themselves and explain their role from the outset.

Staff worked on strategies to create cohesion and a sense of belonging online. With participants meeting from home, there are more potential distractions than in the clinic environment. Patients and clinicians may be preoccupied for a variety of reasons. Challenges may include:

Strong Recovery staff were reminded to set boundaries and eliminate distractions for patients and themselves: conducting meetings in a private room, using headphones if helpful, and taking measures to avoid interruptions.

Keeping these practices in mind may help ease the transition:

Being honest about the challenges of this shift, which is a learning process for everyone

Sharing experiences with telework and creating a sense of relatability with patients adjusting to the new format

Therapist Charles Brown leading a group session through videoconferencing

Increasing engagement

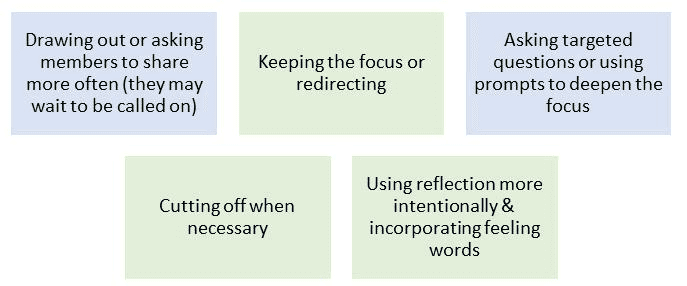

Therapists at Strong Recovery used a more active style as an online group got going to set the culture and increase engagement. Techniques included:

In a virtual space, the therapist may need to take extra steps to become attuned to clients’ reactions or what they might not be saying. Examples of prompts to encourage engagement include:

“I wanted to go back to what Maria shared a few minutes ago. What were people’s reactions to this?”

“Mike, I’m wondering what else you might be willing to share about how you’re handling the situation with your family.”

“Who in the group can relate to Jennifer? Please share with us.”

“It is feeling like the group is a little bit distracted today. What’s going on? Let’s talk about it. On a scale of 1 (bad) to 10 (awesome), how are people feeling about being in group today?”

Therapists were attentive to the impact of the COVID pandemic on patients. Even if they were doing well before, patients were likely struggling in some way—with grief, loss, fear, confusion. Therapists’ expectations for a session had to be flexible enough to accommodate what patients needed at the time. Working with the meeting host, they could conduct risk assessments to inform treatment.

Security and confidentiality

Telehealth guidance on topics such as informed consent, confidentiality, data security, and interjurisdictional practice provide a foundation for providers.¹¹ Programs should be sure to choose a HIPAA-compliant platform for virtual sessions and research telehealth regulations in their state and, if different, the state where their patients live. (Licensing requirements to provide treatment across state lines are an additional consideration.)

Strong Recovery used a Zoom Education license with a modification for HIPAA compliance. Zoom was integrated into the secure electronic health record platform (EPIC).

To address the issue of individuals who were removed from the program (“no return” status), a new meeting link was generated for group members weekly. Participants entered a virtual waiting room when they clicked on a meeting link, then were admitted individually by the host. The host further supported confidentiality by remaining aware that there might be other individuals in a group member’s household. The host was prepared to contact the member if another person appeared while a meeting was taking place.

Strong Recovery considered permitting people to attend groups without using video. They decided video participation was important, however, to support communication, accountability, and trust. This requirement is an obstacle for patients who do not have a camera, and other programs may wish to allow participants to join using audio only.

By utilizing video-platform settings and taking other measures, staff can support privacy.

Steps to support privacy:

Sending a new meeting link for each group

Enabling the waiting room feature

Turning off private chats

Advising patients not to use their full name in the platform

Establishing group norms related to confidentiality

Providing individual reminders as needed (host responsibility)

Measuring success, looking ahead

Attendance at online groups grew over the first several weeks they were offered, with 64 visits the first week, 93 the second, and 115 the third. The program conducted an assessment of no shows through follow-up calls. This initiative helped engage several patients, but it did not result in increased attendance. A proactive approach was then taken that proved more successful: Hosts and therapists started providing on-the-spot reminders, calling patients right before the group and helping them with the meeting link as needed.

Staff were dedicated in troubleshooting technical issues and engaging patients through the video platform. This care made the transition easier. But some patients did not have the means or ability to participate online. Barriers can include lack of a smartphone or computer, lack of internet, or inability to find a private space to meet. Strong Recovery found that therapy by phone and/or in person remained critical for patients who could not take part in video-based therapy during the COVID pandemic.

Achtyl observed that videoconferencing groups appealed to some patients, but not to others. Some preferred to meet in person; others saw the virtual environment as a fresh opportunity. Some people with social anxiety felt more comfortable at home, for example, and some patients with transportation barriers or childcare responsibilities found it easier to join remotely. Videoconferencing emerged as a way to expand participation, but not a good fit for every person.

Therapists noted that videoconferencing from home could inspire new kinds of connections. Patients introduced their pets in group and shared artwork or other projects they were proud of. These moments could lead to conversations about coping skills. “Patients can get to know each other in a deeper way,” Achtyl said, as they join from home—with a movie poster hanging on the wall, a craft project or favorite book nearby, or possibly a cat walking through.

Seche described video-based services as “added pathways to connecting with our patients.” He and Achtyl saw videoconferencing groups open doors to patients who could more easily or comfortably attend. As the situation around COVID allowed, they reinstated some in-person groups and operated under a hybrid system. Gathering input on patients' needs and utilizing therapists’ strengths were essential to these processes. Born of necessity during the pandemic, videoconferencing groups pointed to opportunities for a more connected future.

Program leaders

Julie Achtyl, MS, LMHC, Master-CASAC, NCC

Julie Achtyl is the Program Director of the Strong Recovery Outpatient Clinic and a Clinical Coordinator at the University of Rochester Department of Psychiatry. A certified trainer in Clinical Supervision Foundations II in New York State, Julie blends her passions of counseling, leadership and teaching through training professionals and teaching at CASAC programs. She has also taught courses in group counseling and individual treatment planning.

Patrick Seche, MS, CASAC

Patrick Seche is the Senior Director of Addiction Services and a Senior Associate faculty member in the University of Rochester Medical Center’s Department of Psychiatry, and currently oversees three clinics at Strong Recovery, which is a part of Strong Memorial Hospital. On the steering committee for the University of Rochester’s Recovery Center of Excellence, Patrick focuses on substance use disorder, methadone treatment, and community relations.

Notes

[1] Lin, L., Casteel, D., Shigekawa, E., Weyrich, M.S., Roby, D.H., McMenamin, S.B. (2019). Telemedicine-delivered treatment interventions for substance use disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 101, 38-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.03.007

[2] Lo Coco, G., Melchiori, F., Oieni, V., Infurna, M.R., Strauss, B., Schwartze, D., Rosendahl, J., Gullo, S. (2019). Group treatment for substance use disorder in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 99, 104-116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.01.016. The review suggests there has not been sufficient research on specific group-based interventions or specific SUD populations to draw more nuanced conclusions.

[3] Childs, A.W., Klingensmith, K., Bacon, S.M., Li, L. (2020). Emergency conversion to telehealth in hospital-based psychiatric outpatient services: Strategy and early observations. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113425, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113425 (includes supplement with a detailed telehealth workflow); Childs, A.W., Unger, A., Li, L. (2020). Rapid design and deployment of intensive outpatient, group-based psychiatric care using telehealth during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 27(9), 1420-1424, https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa138

[4] Hom, M.A., Weiss, R.B., Millman, Z.B., Christensen, K., Lewis, E.J., Cho, S., . . . Björgvinsson, T. (2020). Development of a virtual partial hospital program for an acute psychiatric population: Lessons learned and future directions for telepsychotherapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 30(2), 366-382. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000212

[5] Marmarosh, C.L., Forsyth, D.R., Strauss, B., Burlingame, G.M. (2020). The psychology of the COVID-19 pandemic: A group-level perspective. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 24(3), 122-138. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/gdn0000142. Quotation is on p. 133.

[6] Banbury, A., Nancarrow, S., Dart, J., Gray, L., Parkinson, L. (2018). Telehealth interventions delivering home-based support group videoconferencing: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(2), e25. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8090

[7] Gentry, M.T., Lapid, M.I., Clark, M.M., Rummans, T.A. (2018; 2019). Evidence for telehealth group-based treatment: A systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 25(6), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X18775855. Quotation is from the conclusion.

[8] Gentry et al. describe these formats.

[9] Similar to Strong Recovery’s use of hosts, the group-based telehealth described by Childs, Klingensmith, et al.; Childs, Unger, and Li; and Hom et al. had two group leaders, one who conducted the group while the other provided behind-the-scenes support to patients requiring one-on-one intervention or having technical difficulties.

[10] Lo Coco et al. discuss evidence that group therapy promotes sobriety.

[11] Joint Task Force for the Development of Telepsychology Guidelines for Psychologists. (2013). Guidelines for the practice of telepsychology. American Psychologist, 68(9), 791-800, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035001; Shore, J.H., Yellowlees, P., Caudill, R., Johnston, B., Turvey, C., Mishkind, M., . . . Hilty, D. (2018). Best practices in videoconferencing-based telemental health, April 2018. Telemedicine and e-Health, 24(11), 827-832, https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2018.0237

Originally published December 2020, updated July 2025